In The Field: Conversations With Our Contributors—Ty Chapman

Congratulations on being nominated for the Pushcart Award for your poem “Pantheon” in volume 25. This poem speaks not only to the multifaceted layers of oppression Black people face, but also to their divinity. What do you hope readers will take away from this powerful poem?

Thank you!

There’s certainly a part of me that wants to say something along the lines of the author is dead, and I trust readers to interpret the work however they deem best.

However, that’s not a very good answer, and is perhaps a cop out, so I’ll do my best to speak to my intentions while writing this poem. I wanted to speak to the robust history of violence against Black folks present within my community, and within the nation. I wanted to speak to the hurt I, and many other Black folks, carry daily, without presenting us only as our sorrow. Black folk are so much more than sorrow–I think to flatten my people to that one layer of complexity would be yet another act of violence. I wanted to invite sorrow, rage, joy (as resistance,) pride, godhood, and everything between, to share space on the page.

This is partially because I believe contrasting emotions serve to heighten one another in art. Much like in life, if there were no context of sorrow, how would we know joy? I also feel this is the only way to accurately speak to the issue at hand; because the human experience is that of hills and valleys, of finding pockets of warmth to cling to even as the earth is dying. Even as our people are dying. So, I suppose I hope readers walk away with all that (ha.)

Even moreso, I hope readers walk away questioning what “justice” looks like in this country. How the punishing of one cop is a raindrop in the ocean. How we need to do more. How anything less is committing ourselves to more stories that end with a neck on concrete.

“Pantheon” also contains the phrase that ended up being the title for Volume 25, “How Quiet Burns.” Our team of editors selected phrases throughout the collection which could work to tie all the pieces into a cohesive whole. Your line ended up being the one chosen. What does the phrase “how quiet burns” signify for you?

That phrase, and to an extent the poem itself, is a response to the cyclical performativity I’ve noticed in relation to hate crimes. When a particular injustice is trending, folks are quick to take a selfie at a protest, quick to make their avi a black square, quick to scream from the mountaintops that they supported a Black business for the first time the other day. But when it’s not, when there’s no societal pressure pushing folks to be vocal, there’s a ton of silence. It feels like every other day there’s some fresh heartbreak in the news and folks are just content to not engage with it. Meanwhile that’s someone’s neighbor, child, sibling, parent, friend, lover being brutalized by police, or by amateur cop aspirants. The collective apathy, the decision that millions make simultaneously to just turn away, it’s profoundly painful for folks who have experienced prejudice. That shit hurts. It burns. It kills.

The poem “Philophobia: An Heirloom” also included in V. 25 is another powerful piece about a “fatherless son” and how family dynamics become cyclical, making it hard to be vulnerable enough to love, and strong enough to father. I was really taken by this poem’s melancholic reflection. What was your process like in creating this poem?

Yeah, this was a hard poem to write if I’m being honest. It came about partially in reflecting on my own complex family dynamics–the history present there. How a fatherless father can make the decision to leave his child fatherless–how much pain and fear must plague a person in order to make that sort of decision. How trauma travels down a lineage.

Writing this poem, which is as much about my father, and his, as it is about myself and my own shortcomings, felt like both a practice in radical compassion and honest self reflection. More than that though, this is a poem about love. About this misconception, that I think many of us hold in our bodies, that love is a force to fight against. That such vulnerability only represents the potential for pain. And of course, as you say, how cyclical this history of little violences can become. How so many of us hurt those we claim to care for in a bid to protect our most vulnerable parts.

Additionally, it was a slight experimentation with form. This poem was heavily inspired by Jericho Brown’s Duplex form, though it is not quite a proper duplex. I sort of decided to pick and choose elements, (the couplets and repetition) without keeping everything. Jericho called the duplex “a mutt of a form.” So I guess I’d say this poem is a bastardization of the mutt (ha.)

That’s all a wordy way of saying my process was 2 parts reflection, 1 part form.

You are also a writer of children’s books. I recently gifted a copy of your picture book Sarah Rising to a  youngster close to me. This book talks about a young girl who participates in a protest against police brutality with her father. “Pantheon” as well tackles police brutality and racism, referring to George Floyd’s last words “All he wanted was his momma.” What are your thoughts on how literature can affect social change?

youngster close to me. This book talks about a young girl who participates in a protest against police brutality with her father. “Pantheon” as well tackles police brutality and racism, referring to George Floyd’s last words “All he wanted was his momma.” What are your thoughts on how literature can affect social change?

There’s a lengthy history of literature being in conversation with social movements, inspiring them, reminding people of their shared humanity, of what we cannot tolerate as human beings. There’s a reason totalitarian regimes target the artists. There’s a reason nazis burned books. There’s a reason individuals in our country essentially seek to accomplish the same goal via bannings. I think books, written with care, are inherently dangerous to those who would seek to divide and conquer–those who would seek total control on the false basis that some folks are less human than others–less deserving of stories or compassion. Art has always had a deep home in social justice movements. Is my poem going to change America? Nah. Is Sarah Rising? Probably not. But I believe that art can be a drop in the bucket; a tool for gradual change, in conjunction with folks standing side-by-side to demand justice.

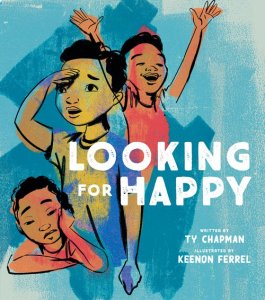

You have three picture books Sarah Rising, A Door Made for Me written with Tyler Merritt, and coming soon Looking for Happy. What draws you to the art form of writing books for children?

On one level, writing for children feels like an attempt at an intervention. Children are birthed with so much love in their bodies. It feels perhaps cliche to say, but children must be taught to hate. So, to a certain extent, I write for children to offer an alternative to hate at a time where humans are still open to new ideas. We become so walled off and rigid as we grow– unwilling to consider the stories of others, or consider that we might carry harmful and false notions with us.

unwilling to consider the stories of others, or consider that we might carry harmful and false notions with us.

I think early childhood, in so many ways, is the perfect time for an intervention. To center an alternative to hate.

On another, and even more crucial level, I write to kids in a bid to provide light and support to children living through absolutely terrifying times. In considering the future, I feel immense fear–so I can only imagine how our current world weighs on the youth. I want to remind the youth, especially Black youth, that there are folks who will look to protect them, that there are still reasons to smile as well as reasons to stand up and demand better. I adore writing to kids because it gives me an opportunity to center the stories I desperately needed, and did not have growing up.

In addition to being a writer, you were also a puppeteer. Do you intend to work as a puppeteer in the future? How did the artistry of puppetry shape you as a writer?

Puppetry put me back in touch with my roots as an artist. I began experimenting with the form at a time when I was working two other jobs (behavior management in an educational setting, and food running because educators never get paid enough) and I was positively joyless. Reconnecting with the arts through puppetry and theater reminded me to demand agency in my life, to center storytelling above all else.

Additionally, writing for the form has an absurd amount of overlap with writing picture books–only I didn’t have a  remarkable team of editors, agents, and publicists backing me up when I was writing puppet shows (thank you editors, agents, and publicists.) The two forms feel intrinsically linked. Much like a puppet, picture book characters go through one action at a time, typically having a single focus or desire per spread. Much like puppet shows, picture books are an incredibly visual form. In both forms, dialogue and exposition must sometimes take a backseat to the stunning visuals they’re known for. Other times, they very much must not. The balancing act present in both forms feels very similar.

remarkable team of editors, agents, and publicists backing me up when I was writing puppet shows (thank you editors, agents, and publicists.) The two forms feel intrinsically linked. Much like a puppet, picture book characters go through one action at a time, typically having a single focus or desire per spread. Much like puppet shows, picture books are an incredibly visual form. In both forms, dialogue and exposition must sometimes take a backseat to the stunning visuals they’re known for. Other times, they very much must not. The balancing act present in both forms feels very similar.

Regarding a return to the stage, I’ll never say never, but creating both as a poet and fiction author feels like a full time gig and then some. I still love the form, and would love to write a show and let other people perform it some day, but I think my time center stage might be behind me (short lived as it was.)

You are a Loft Literary Mirrors and Windows fellow and a Mentor Series fellow. Could you explain a little about this work and opportunities that these awards provided for you as a writer?

BIG shoutout to Dr. Sarah Park Dahlen, Molly Beth Griffin, Bao Phi, and The Loft Literary Center. I owe them my career. Mirrors and Windows was a life changing experience for me. I probably wouldn’t be a children’s book author if not for that fellowship teaching me the ins and outs of writing for the form, and what to expect as a person of color navigating the publishing business. I certainly wouldn’t have a few books out with more on the way.

Mentor series also felt helpful! It put me in touch with talented authors who helped me refine my craft. My forthcoming debut poetry collection grew a lot during my time in the Mentor Series, learning from incredible mentors like Shannon Gibney, Anika Fajardo, Chris Santiago, and more.

But also, engaging with The Loft’s other programming has helped me develop as a writer and professional as well. Taking months of poetry classes with Gretchen Marquette (as well as borrowing an ungodly number of books from Danez Smith, unrelated to The Loft) in 2020 helped me begin my poetry collection (then in the form of a chapbook) submitting a previous version of the collection to Sun Yung Shin for manuscript critique in 2021 helped it grow enough to be longlisted in Button Poetry’s chapbook contest. My time in the Mentor Series helped me develop stronger work, and make the leap from chapbook-in-progress to full length collection-in-progress.

Art making, like baby raising, takes a whole village. The Loft played a huge role as I cobbled mine together.

You have a forthcoming poetry collection through Button Poetry. What themes are you tackling through your poetry, and when can we expect to get our hands on it? What else are you working on?

Thematically, I think the two poems published through Water~Stone are a solid representation of the greater collection being published by Button. It goes in depth with the same themes: systemic racism, social justice, love, loss, loneliness, existentialism, nihilism, joy, hope, and all their intersections. Also rage. Can’t forget the rage. Many of the thoughts, experiences, and sentiments that wouldn’t be thematically or developmentally appropriate for my kidlit work found their way to my poetry collection, so I think there’s a decent spread.We’re still working on it, so it’ll be a while. Look for that collection in 2024.

One might say I’m doing too much.

I’m currently pursuing an MFA in creative writing for children and young adults at Vermont College of Fine Arts, and that’s keeping me busy. It has been a great opportunity to experiment with new forms, genres, voices, and age ranges, so I hope to have fun developments on that front eventually. Additionally, I’m working on a collaborative picture book with my dear friend John Coy, my next solo picture book that I can’t speak on too much yet, and wrapping up the process on Looking for Happy, which comes out May 2023.

TY CHAPMAN is the author of Sarah Rising (Beaming 2022); Looking for Happy (Beaming 2023); A Door Made for Me, written with Tyler Merritt (WorthyKids 2022); Tartarus (Button Poetry 2024); and multiple forthcoming children’s books through various publishers. Chapman was a finalist for Tin House’s 2022 Fall Residency, Button Poetry’s 2022 Chapbook Contest, and Frontier Magazine’s New Voices contest. Chapman’s accomplishments also include being named a Loft Literary Center Mirrors and Windows fellow and a Mentor Series fellow, and attending Vermont College of Fine Arts in pursuit of his master’s degree in creative writing for children and young adults.

TY CHAPMAN is the author of Sarah Rising (Beaming 2022); Looking for Happy (Beaming 2023); A Door Made for Me, written with Tyler Merritt (WorthyKids 2022); Tartarus (Button Poetry 2024); and multiple forthcoming children’s books through various publishers. Chapman was a finalist for Tin House’s 2022 Fall Residency, Button Poetry’s 2022 Chapbook Contest, and Frontier Magazine’s New Voices contest. Chapman’s accomplishments also include being named a Loft Literary Center Mirrors and Windows fellow and a Mentor Series fellow, and attending Vermont College of Fine Arts in pursuit of his master’s degree in creative writing for children and young adults.