In the Field: Conversations With Our Contributors–Jeanette Beebe

In the Field: Conversations With Our Contributors–Jeanette Beebe

Tell us about your poem “[TK]” in Volume 22. How did it come to be?

“[TK]” is a broken sonnet. It’s dedicated to the journalists who kept working during and after the mass shooting at The Capital Gazette’s newsroom in Annapolis, Maryland on June 28, 2018. They “never stopped doing their jobs,” Matthew Haag and Sabrina Tavernise wrote in The New York Times the day after the tragedy. Four journalists — Gerald Fischman, Robert Hiaasen, John McNamara, and Wendi Winters — were killed alongside Rebecca Smith, a sales representative. The Capital Gazette later won a special Pulitzer Prize citation for “demonstrating unflagging commitment to covering the news and serving their community at a time of unspeakable grief.”

What excites you as a writer?

The place of intersection between the two modes of writing that define my life — poetry and journalism; that’s what motivates me. To try to tell fully-formed nonfiction stories in journalistic verse. To try to write poems that do what journalism does. To try to make ‘the news’ accessible to people who’ve stopped paying attention to it, because it can seem endless and overwhelming. To write not just to figure it out, but to linger, to reveal.

The place of intersection between the two modes of writing that define my life — poetry and journalism; that’s what motivates me. To try to tell fully-formed nonfiction stories in journalistic verse. To try to write poems that do what journalism does. To try to make ‘the news’ accessible to people who’ve stopped paying attention to it, because it can seem endless and overwhelming. To write not just to figure it out, but to linger, to reveal.

What craft element challenges you the most in your writing? How do you approach it? What is your quirk as a writer?

Like my journalism, my poems work to investigate, to scoop, but they also get lost and meander, too. They weave in and out. And the way a poem works is a mystery. It’s so rarely a wrap-up, a nut-graf. The form of the things often reflects the emotion at its center. As Emily Dickinson wrote, “Tell all the truth but tell it slant.” If that’s what you sign on for, then you have to be patient. You have to trust that something is going to happen, that there’s a there there that you should wait for, and try to understand.

Do you practice any other art forms? If so, how do these influence your writing and/or creative process?

I’m a stage-to-page poet who grew up in the slam poetry world. I’m also an audio journalist who works as a freelance reporter and recordist/producer. Together, these worlds have given me a deep respect for the spoken word. Because when we hear someone’s voice, we feel what they’re saying. Sound is crucial. It’s essential for explaining, and also for being understood — which is why many of us write in the first place.

What was an early experience that led to you becoming a writer?

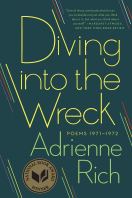

The first book of poems I ever owned was a reluctant gift — not stolen, technically — from my high school library in Iowa: Adrienne Rich’s Diving Into the Wreck. It was the mid-aughts. The card pasted to the first page of the book was stamped with its last reader: April 23, 1998. So it wasn’t a popular volume. But it mattered to me.

The first book of poems I ever owned was a reluctant gift — not stolen, technically — from my high school library in Iowa: Adrienne Rich’s Diving Into the Wreck. It was the mid-aughts. The card pasted to the first page of the book was stamped with its last reader: April 23, 1998. So it wasn’t a popular volume. But it mattered to me.

In my first semester at Princeton, I was lucky enough to speak with Rich for a good ten to fifteen minutes after she gave a reading on campus. It was magical. And I’d brought my copy with me. The first poem, “Trying to Talk with a Man,” is a clean page. But the second poem, “When We Dead Awaken,” is scrawled over with black pen: awkward, jotted stanzas of my own, on and on throughout the book. Half pen, half printed text.

Rich seemed surprised when she saw it. “You wrote in a library book?” she said. Yes, I nodded. And fortunately, my creative writing teacher, Ms. Karen Downing — the teacher who got me writing in the first place, the person who changed my life, forever — decided to simply give me the book after flipping through marked-up page after page.

“Do you mind that I wrote in it?” I asked. “I love people writing in my books,” she replied. “It shows that you actually read it.” With the good fortune of being the last person in line, I managed to ask her a few more questions about her own journey as a young poet. She recalled something from her time at Radcliffe that stayed with her. In a seminar, Theodore Morrison once quoted Chaucer’s “The Assembly of Fowls”: “The life so short, the craft so long to learn,” she said. When I sighed, she said, “You asked, and I told you.”

Jeanette Beebe was a finalist for the 2019 Iowa Review Award in Poetry and a semifinalist for the 2019 92Y Discovery Poetry Contest. A Best New Poets- and Pushcart-nominated poet and journalist, she holds an A.B. from Princeton, where she was lucky enough to write a thesis advised by Tracy K. Smith. Her poems have appeared or are forthcoming in Poet Lore, Bayou Magazine, Juked, New South, South Dakota Review, The Chattahoochee Review, After the Pause, Tinderbox Poetry Journal, and elsewhere. Her first publications were stage-to-page poems Xeroxed and stapled in chapbooks to support her hometown poetry slam in Des Moines, Iowa — a journey that led her to the Brave New Voices Youth Poetry Slam as a member of Minnesota’s inaugural team. She is based in New Jersey. You can learn more about her work at her website www.jeanettebeebe.com.

In The Field: Conversations With Our Contributors–Tessa Livingstone

In The Field: Conversations With Our Contributors–Tessa Livingstone

Tell us about your poem “The Mystic Explains” in Volume 22. How did it come to be?

Tell us about your poem “The Mystic Explains” in Volume 22. How did it come to be?

“The Mystic Explains” was inspired by my favorite Tarot card, the Eight of Cups, which is said to represent things thrown aside as soon as they’re gained (i.e., success abandoned). I was thinking about how the card corresponds not just to the human world, but to the world of nature as well. The idea that even an animal gets what it wants at some point—in the poem’s case, a prized racehorse. I thought it would be interesting to contrast that with the speaker, who has suffered a stillbirth. There is an underlying absurdity in the mystic’s command: “When you get what you want, you must give it up.” I wanted the speaker to refute the idea that everyone gets what they want and has a choice in letting go, with the last two lines being directed at both the mystic and the reader.

What excites you as a writer? What turns you off, makes you turn away or stop reading a piece of writing?

Description really excites me— how it can create a subjective kind of seeing, and make images new. One of my favorite images ever comes from The Bell Jar when Sylvia Plath’s speaker describes the impact of seeing a cadaver for the first time: “For weeks afterward, the cadaver’s head—or what was left of it—floated up behind my eggs and bacon at breakfast and behind the face of Buddy Willard, who was responsible for my seeing it in the first place, and pretty soon I felt as though I were carrying that cadaver’s head around with me on a string, like some black, noseless balloon stinking of vinegar.” I love that descriptive language has the power to extend and illuminate our perceptions, and typically veer away from writing that doesn’t indulge this.

What are some themes/topics that are important to your writing?

I’m most interested in the transformative and macabre, motherhood, irreversible loss, abandonment, and choice within choicelessness.

Do you practice any other art forms? If so, how do these influence your writing and/or creative process?

I learned how to play the musical saw about the same time I started my MFA program. Somewhere in the Appalachian mountains, in the early 19th century, rural southerners discovered you could produce ethereal sounds by bending the blade of a common carpenter’s saw and bowing along its flat edge. It sounds sort of like a Theremin, or an opera singer, or a ghost wooing in a B-horror movie. It’s gorgeously eerie. Learning the musical saw greatly informed my creative process because there are technically no rules to it. You can learn how to hold it correctly, how to bend the blade and how to bow, but the music itself is learned by ear and through muscle memory. There are no set notes or sheet music, but a range of limitless, expressive possibilities.

I learned how to play the musical saw about the same time I started my MFA program. Somewhere in the Appalachian mountains, in the early 19th century, rural southerners discovered you could produce ethereal sounds by bending the blade of a common carpenter’s saw and bowing along its flat edge. It sounds sort of like a Theremin, or an opera singer, or a ghost wooing in a B-horror movie. It’s gorgeously eerie. Learning the musical saw greatly informed my creative process because there are technically no rules to it. You can learn how to hold it correctly, how to bend the blade and how to bow, but the music itself is learned by ear and through muscle memory. There are no set notes or sheet music, but a range of limitless, expressive possibilities.

What projects or pieces are you working on right now?

I’ve been working on my first poetry book, Lady Grimm, for the past two or three years now. It’s a conceptual assemblage of fairy tales, fables, and nursery rhymes that center around a stillbirth in 1940s Scotland. It is both true and all made up.

Tessa Livingstone is a poet who holds an MFA from Portland State University. Her poems have appeared in Geometry, FIVE:2:ONE, Whiskey Island Magazine, and Portland Review, among others. Her poem “Grant, 1970” won the Blue Earth Review 2018 Poetry Contest, and was featured in their Fall 2018 issue. You can find her on Twitter @livingstonepoet.

In The Field: Conversations With Our Contributors–Ed Bok Lee

In The Field: Conversations With Our Contributors–Ed Bok Lee

Tell us about your fiction piece “The Ferryman” in Volume 22. How did it come to be?

This short story about a group of Asian American friends (from all different cultural and ethnic backgrounds) is one of a dozen or so that I’ve had for some time. They are interlinked stories, so the characters do reappear throughout the collection. I put the stories away several years back because, at the time, no one – the editors and publishers I showed them to, at least – seemed interested in these people and their lives. But more to your question, it’s not always clear where something comes from. I do remember I was bartending and working in a homeless shelter around the time I first started working on them. And bars and shelters and halfway houses factor into a number of the stories.

What excites you as a writer? What turns you off, makes you turn away or stop reading a piece of writing?

What excites you as a writer? What turns you off, makes you turn away or stop reading a piece of writing?

The possibility of being transported and changed molecularly always excites me. Every new book I pick up has the possibility of doing that. As I’ve noted elsewhere, sometimes, if things aren’t going well with the writing, I’ll start reading a book that I truly admire and also can’t get into. After reading for a while, my mind gets pitched into the perfect state for a new creative act. My mind feels cleansed. I suspect this is connected to my fundamental reverence for books, which at some irrational level I feel are all sacred. Someone was, at some level, having a sacred conversation with themselves, or, more precisely, trying to resolve a quarrel deep within and employing sacred methods in the creation of this book. And so, when I’m reading a book I truly admire but never manages to capture me, the world just feels slightly off. I go into a mode of needing to make what I’m doing on my own page work, to try to get things back into some sort of alignment. So even the books that I can’t get into are sometimes incredibly useful.

What was an early experience that led to you becoming a writer?

Threads – Trang T. Le

Librarians and used book store clerks leading up to the time I started writing were very important. But on a deeper level, reconnecting with my past was also seminal. My father’s mother, my halmoni, was a poet. At a time when I was first learning to form sentences in Korea, she looked after me. In part because of the old style of Korean that she spoke in, and also because she was a strange person and spoke of strange things, everything about her was weird and mysterious and miraculous to me. She had many shamanistic beliefs. This was the 1970s in South Korea, under the dictatorship of Park Chung-hee. The government was rounding up poets and writers and intellectuals, imprisoning and beating some of them to the point of brain damage. My grandmother wrote deeply personal poems. But her written Korean was fairly unformed. Korean wasn’t really taught back then, especially to girls. Years later, when I began studying, then translating Korean poetry, all these personal and social memories started to come back: Tanks and military personnel stationed, due to the ever-impending threat of another invasion from North Korea. Enforced curfew under martial law throughout Seoul and the nation. All the symbolism and paraphernalia and infrastructure that go along with Western colonialism and imperialism of a much poorer nation, all began coming back or blooming, as if from seeds that had first been planted wordlessly in me as a kid.

Do you practice any other art forms? If so, how do these influence your writing and/or creative process?

I write poems, stories, plays, essays, and have worked on public literary arts projects, such as transforming a 100-car municipal parking lot in Lanesboro, MN into a “Poetry Parking Lot.” In general, I think if you try to live your life as artfully (and that will mean different things to different people) as you can, things just sort of flow out of you. And if they don’t flow, yet you’re trying your best to be as true to who you are as you can, they sort of begin to secrete as if from fractures or leaks. And those secretions begin to transform everything good for art in your life, while also warding off all that is bad for art in your life. This isn’t always what the individual wants, or thinks they want. But it’s what the art wants. Some people put up a really good fight their whole lives, though. I think what I’m talking about is: giving over to something and not caring what form it takes, not operating from any socially conditioned notions or expectations.

What are some themes/topics that are important to your writing?

What are some themes/topics that are important to your writing?

In prose, what it means to be human; in poetry, what it means not to be.

What does your creative process look like? How does the environment you are in shape your work or where do you like to write?

A wildfire. . . or else a damp, barely smoldering something with too much noxious gasoline thrown uselessly onto it.

What projects or pieces are you working on right now?

Now that I’m coming off of a bunch of travel and other things related to my most recent book of poetry, Mitochondrial Night, I’m writing more: poems, and I’m almost finished with a somewhat experimental novel.

Ed Bok Lee is the author of three books of poetry, most recently Mitochondrial Night (Coffee House Press, 2019). Honors for his work include an American Book Award, Minnesota Book Award, Asian American Literary Award (Members’ Choice), and a PEN/Open Book Award. He also works as an artist and translator, and for two decades has taught in programs for youth and the incarcerated. You can learn more about Ed’s work at his website.

In The Field: Conversations With Our Contributors–Morgan Grayce Willow

In The Field: Conversations With Our Contributors–Morgan Grayce Willow

Tell us about your CNF piece “(Un)document(ing)” in Volume 22. How did it come to be?

I had been trying to come to terms with my own complicity in the theft of land from Native peoples. Each time I tried writing about it, I discovered that the notion of land ownership was embedded in ever-deeper layers of my emotional life and psyche. Meanwhile, some years ago I had done a fair bit of genealogical research, gathering documents – print documents, copies, etc. before the ubiquity of the internet, before Ancestry.com and so on – about my ancestors. In graduate school, I’d taken a class in the American 1890’s in which one of our assignments was to research how our own families – and, hence, ourselves – fit into the Zeitgeist of the period. So my task was to make some sense of the documents I’d gathered – land deeds, bills of sale, maps, etc. I later supplemented all that with internet sources, including, for example, Google Maps which gave me a current view of the farm I grew up on.

I had been trying to come to terms with my own complicity in the theft of land from Native peoples. Each time I tried writing about it, I discovered that the notion of land ownership was embedded in ever-deeper layers of my emotional life and psyche. Meanwhile, some years ago I had done a fair bit of genealogical research, gathering documents – print documents, copies, etc. before the ubiquity of the internet, before Ancestry.com and so on – about my ancestors. In graduate school, I’d taken a class in the American 1890’s in which one of our assignments was to research how our own families – and, hence, ourselves – fit into the Zeitgeist of the period. So my task was to make some sense of the documents I’d gathered – land deeds, bills of sale, maps, etc. I later supplemented all that with internet sources, including, for example, Google Maps which gave me a current view of the farm I grew up on.

This thread converged with the current ethos of crisis about immigration, what immigration means to me personally and to us as a nation. So many are descended from immigrants, and survival has come at the expense of Indigenous peoples, who had been forced to migrate. It all felt so complicated, muddled, and painful. Writing the essay – finding a form to contain the layers – was an attempt to make sense of all this for myself. I set out to assay, or interrogate, the documents. What does it mean to be documented? What are documents? Which ones count and which ones don’t? Who gets to decide? etc. It was a way to name how my own personal narrative intersects with – and is partially culpable for – the historical narrative as represented in documents.

What was an early experience that led to you becoming a writer?

I didn’t really know that being a writer was something a person could do. Growing up on a small family farm, I didn’t have any role models for a writing life. Farm life is all about work. I do remember, however, falling in love with language. We had very few books in the house, but we did have a big, fat, black-covered dictionary. I recall pretending to read it before I actually knew how. I’d sit with it on my lap – my feet sticking straight out on the couch – and open its pages. At first, I often had the book upside down, but that didn’t stop me from running my fingers along the columns and saying words as though they were the words I was looking at. Fortunately, that dictionary – desk size, but it felt like an unabridged to me – did have lovely engraved illustrations. Once I figured out the pictures, I got the orientation of the book right. Eventually, as I learned the letters of the alphabet, I realized that the book followed that same order. Each “chapter” had a letter for its title. The order and accumulation of the words fascinated me. That early love of language, and subsequently reading, laid the foundation, I think, for becoming a writer. I still love an actual, physical dictionary, though my Merriam-Webster app is one of the most-used apps on my cell phone.

Do you practice any other art forms? If so, how do these influence your writing and/or creative process?

You’ve used the word practice, which tempts me to mention Tai Chi. I’ve practiced Tai Chi for more than a quarter of a century. I consider it one of the great gifts of my younger self to my current self that I started to practice and have kept it up, albeit in varying degrees and configurations over the years. Doing so, of course, helps with health and sanity, but it also supports my creative process by allowing me to think of writing as a practice, to focus on doing as much, if not more, than on product. If I focus too much on the product, I risk falling prey to perfectionism, which can very quickly stymie my writing.

I have also in the last several years become involved with book arts through workshops and classes at Minnesota Center for Book Arts (MCBA). I completed their core certificate, which meant taking a balanced series of courses in bookmaking, printing, and paper making. The book arts gets me out of my head and literally onto the page – the made, printed, folded, stitched, or collaged page. They let me get my hands dirty and ground me in tactile experience. They nurture creativity in nonverbal ways, and sometimes they present opportunities to put some of my own text out into the world through a physical process.

What craft element challenges you the most in your writing? How do you approach it? What is your quirk as a writer?

Form, I suppose, challenges me the most – finding the form that best suits the particular message or moment that needs expression. Sometimes I experiment with form, and the form leads me to language for expressing things I didn’t know I needed to say. Other times, I have something in mind or gut that needs saying, and I have to try out whether it’s best said as a poem or an essay. And once I’ve found the genre that seems to be the right container, then the choices narrow – or broaden – to language, shape and sound . . . not in any particular order. It’s a recursive process of trying this and listening to that, and so on.

As to my quirks as a writer, my writing group can probably identify those better than I can, although one of them may be how I use journals and notebooks in my process. I’d be lost without them.

What does your creative process look like? How does the environment you are in shape your work or where do you like to write?

I often wish I were more organized; however, my creative process is anything but. I admire writers and artists who work with intense focus on a single project at a time. But for me, images, ideas, phrases or titles come at me like the weather – unpredictable and getting wilder all the time. I keep track of the floods of them in my journals and notebooks – lists, notes, indexes, etc. Then during dry spells, I have a storehouse to dip into. I do some writing in the mornings, often in those journals. And I really enjoy sneaking away to my studio, which is separate from my house. It’s mostly quiet there – or at least the sounds are different from home sounds. And there’s no laundry to do there. Plus, I can make a mess – say, with a collage or visual journal – and leave it in process without having to move it off the dining room table.

I often wish I were more organized; however, my creative process is anything but. I admire writers and artists who work with intense focus on a single project at a time. But for me, images, ideas, phrases or titles come at me like the weather – unpredictable and getting wilder all the time. I keep track of the floods of them in my journals and notebooks – lists, notes, indexes, etc. Then during dry spells, I have a storehouse to dip into. I do some writing in the mornings, often in those journals. And I really enjoy sneaking away to my studio, which is separate from my house. It’s mostly quiet there – or at least the sounds are different from home sounds. And there’s no laundry to do there. Plus, I can make a mess – say, with a collage or visual journal – and leave it in process without having to move it off the dining room table.

What projects or pieces are you working on right now?

I have a couple poetry manuscripts – a collection and a chapbook – out searching for a home. While they’re circulating, I’m turning my attention again to the essay form. A number of subjects keep tapping me on the shoulder, reminding me they’re waiting in the wings. They’ve lost patience, so I think I’d better get to them before they decide to wander off. I like the adventure of following an inquiry, exploring it from different angles, finding the right shape and language for it. It’s also a marvelous moment when, after having been working on poems, I get to stretch out across the page and live in that different rhythm that prose makes. I’m looking forward to that.

Morgan Grayce Willow is the author of three collections of poems, most recently Dodge & Scramble. She has received awards in both poetry and creative nonfiction from the Minnesota State Arts Board, the McKnight Foundation, the Jerome Foundation, and the Witter Bynner Foundation. Her essay “Riding Shotgun for Stanley Home Products” is the title piece in Riding Shotgun: Women Write about Their Mothers. Morgan’s essay “Signs of the Time” earned honorable mention in the inaugural Judith Kitchen Prize in Water~Stone Review in 2011.

In The Field: Conversations With Our Contributors–Purvi Shah

In The Field: Conversations With Our Contributors–Purvi Shah

Tell us about your poem “Moving houses, Maya pumps a music that cannot offer” in Volume 22. How did it come to be?

In some ways, I have an unusual New York City story – which is that I’ve lived in my same apartment for 23 years. NYC is a city of transience, a city of temporary destinations. I thought it would be so for me too. And yet, here I am, decades later, now a verified New Yorker. And I am often imagining moving, imagining what it is to pack, what it is to unpack.

Like the poems in my latest book, Miracle Marks, “Moving houses, Maya pumps a music that cannot offer –” draws upon Hindu iconography & philosophy – particularly concepts of sound as creation, the universe as vibration, vibration as constant. I had been pondering ideas of being/non-being, the illusions of life, infinite in the finite, and the mundane boxes of life (even before the unboxing craze!). I had been exploring sound energy, the white space of being and creation, how the physicality of poems is a kind of breath, an imprint, an energy-scape.

What is it to praise the unfinished? What is it to praise? What is it to live – between boxes, between musics? Like many of my poems, this piece came to be in the space of questions, observations, sounds, and wonder.

Do you practice any other art forms? How do these influence your writing and/or creative process?

My mom says there are two things she loves: looking good and dancing. And so I’ve inherited a love of dancing, the body in motion, the body in praise, the body in joy. As I wrote this, we were nearing the end of last fall’s Navaratri, the nine nights of the celebration of the goddess in Hinduism. I grew up dancing garba, a folk dance of Gujarat done during Navaratri, a dance done in a circle. I love garba because it’s fun & energetic – and because it’s a community art. Anyone can garba. Anyone can be part of the circle. Anyone can praise the feminine divine. Garba builds community through joy. This sense of the circle, of lila (divine play) is plaited in my poems.

My mom says there are two things she loves: looking good and dancing. And so I’ve inherited a love of dancing, the body in motion, the body in praise, the body in joy. As I wrote this, we were nearing the end of last fall’s Navaratri, the nine nights of the celebration of the goddess in Hinduism. I grew up dancing garba, a folk dance of Gujarat done during Navaratri, a dance done in a circle. I love garba because it’s fun & energetic – and because it’s a community art. Anyone can garba. Anyone can be part of the circle. Anyone can praise the feminine divine. Garba builds community through joy. This sense of the circle, of lila (divine play) is plaited in my poems.

And though I am not a visual artist, I have collaborated with visual artists, particularly the brilliant Anjali Deshmukh in embodied, public art. In July 2018, we created Weave & Woven, an event that explored home and belonging through interactive art. I had written my poems onto the walls of an art gallery while Anjali had created a magical architecture of arches, domes, and lines with ribbon. We invited folks to write & draw on the walls, learn garba & raas and dance with me, and be part of the art.

I love when art can be community creation, when artists make possible community creation. As the first artist in my immigrant family, I feel deeply a connection to communal art forms. For that reason, I’ve sought out ways to enable writing in community and writing through community.

How does the current political climate influence your art or creative process?

The current political moment is exhausting – and requires connection. I’ve been trying to keep joy, hope, resistance, and community in my practice, which means going to readings (such as fundraisers supporting migrant justice) and book launch celebrations while I do my work as an advocate for gender, racial, and economic justice. I feel a deep responsibility to affirm longings for justice, for possibility while recognizing the resurgence of white supremacy, misogyny, xenophobia, global fascisms (including in my two homelands of the U.S. and India), and oppressions facing us today. We need our truths to resist erasures. And I see creation as life-force, as part of continuing to live and love large, to bring about the world as we hope, the world we & future generations deserve.

What projects or pieces are you working on right now?

I developed more participatory art projects such as “Counting on Women” for Two Minutes to Midnight, a public art event in Sunnyside, Queens exploring climate and gender justice. In a public plaza, I asked folks: How do girls & women count? How do we count on girls & women? And I read excerpts of Miracle Marks in resonance & dialogue with the public wisdom.

I developed more participatory art projects such as “Counting on Women” for Two Minutes to Midnight, a public art event in Sunnyside, Queens exploring climate and gender justice. In a public plaza, I asked folks: How do girls & women count? How do we count on girls & women? And I read excerpts of Miracle Marks in resonance & dialogue with the public wisdom.

October is Domestic Violence Awareness Month, and so I also shared from my work as an anti-violence advocate with book readings at CalArts and the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign. I’m grateful to be creating in community, to be in dialogue with students & the everyday public, and to be moving across spaces, to be moving across possibilities, to be moving.

Purvi Shah won the inaugural SONY South Asian Social Service Excellence Award for her leadership fighting violence against women. During the tenth anniversary of 9/11, with the Kundiman organization, she directed Together We Are New York, a community-based poetry project highlighting Asian American voices. Terrain Tracks, her debut poetry collection on migration and belonging, won the Many Voices Project prize. Her latest book, Miracle Marks, explores women, the sacred, and gender & racial equity. She serves as a board member of The Poetry Project. You can learn more about Purvi’s work at her website, and follow her on Twitter @PurviPoets.