In The Field: Conversations With Our Contributors–Esteban Rodriguez

In The Field: Conversations With Our Contributors–Esteban Rodriguez

1. Tell us about your poem in Volume 20. How did it come to be?

I first wrote the poem “Ventriloquist” when I was living in the Rio Grande Valley.  It’s by no means uncommon to hear English and Spanish (or a combination of both) spoken throughout the region. However, Spanish wasn’t my first language, and it wasn’t necessarily because it was discouraged (as it was in my parent’s generation) as much as it was neglected, placed on the back burner for what I assume my parents thought was the more practical English. The poem is a reflection on my struggles to learn Spanish throughout my childhood, and the hope that, through every Post-It note and botched pronunciation, I could connect with an important part of my culture that always seemed out of reach.

It’s by no means uncommon to hear English and Spanish (or a combination of both) spoken throughout the region. However, Spanish wasn’t my first language, and it wasn’t necessarily because it was discouraged (as it was in my parent’s generation) as much as it was neglected, placed on the back burner for what I assume my parents thought was the more practical English. The poem is a reflection on my struggles to learn Spanish throughout my childhood, and the hope that, through every Post-It note and botched pronunciation, I could connect with an important part of my culture that always seemed out of reach.

2. What was an early experience that led to you becoming a writer?

As a graduate fresh out of college, I was living somewhat aimlessly, unsure what direction life was bound to take me. I started writing as a way to cope with the boredom and it quickly became a habit, then an obsession, and then a way of living. No one experience shaped my inspiration to write, rather, it was the process and struggle of trying to put something on paper that shaped the writer I am today. It’s still a process and it’s still a struggle, but if wasn’t, I know I wouldn’t have anything to say.

As a graduate fresh out of college, I was living somewhat aimlessly, unsure what direction life was bound to take me. I started writing as a way to cope with the boredom and it quickly became a habit, then an obsession, and then a way of living. No one experience shaped my inspiration to write, rather, it was the process and struggle of trying to put something on paper that shaped the writer I am today. It’s still a process and it’s still a struggle, but if wasn’t, I know I wouldn’t have anything to say.

3. How has writing shaped your life?

Short answer: for the better.

4. What books, writers, art, or artists inspire you and your work?

I try to read as much contemporary poetry as possible, but I find myself returning to collections by Bob Hicok, Dean Young, Tony Hoagland, Daniel Borzutzky, and Valzhyna Mort. No other contemporary writer for me, however, creates such poetic (and often nightmarish) landscapes quite like Cormac McCarthy. Each time I reread his novels and plays I discover something new and meaningful about the world I had never considered before, which is what good writing, regardless of genre, is supposed to make its readers feel.

5. What projects or pieces are you working on right now?

I’m currently working on completing two manuscripts, one that extends on the themes and narratives of my first completed manuscript, Portraits from the Orphaned Plains (where “Ventriloquist” appears), and another (still untitled) that centers on war, violence, and the struggle to make meaning through chaos and destruction. Although they differ significantly in content and style, they each allow me to push my writing further, and to say something new about the world and the human condition.

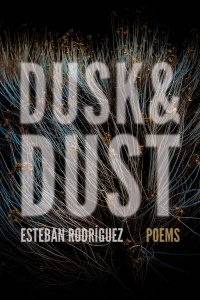

Esteban’s collection of poetry, “Dusk & Dust,” will be published by Hub City Press this coming fall. Learn more about the book here. Pre-order now. Follow Esteban on Twitter.

Poetry Matters, By Jason Ryou

Poetry Matters, By Jason Ryou

Language and communication are essential to life and culture, but where is poetry’s place in a world where the emphasis is on speed and efficiency? If one can get past the notion that poetry is only for intellectuals and scholars, that it is boring and difficult to understand, then becomes apparent the fact that poetry is simply a way to smell the proverbial roses. It can help us appreciate language, how beautiful it can be, how wonderful it can sound. That love of language can then be communicated to readers and spread around the world. Sounds idealistic and romantic, but in my opinion this is actually what poetry can accomplish.

Poetry can encompass both the sound of music and the movement of dance. It can also capture beautiful visual images, and reproduce the rough or smooth texture of things. It records our experiences of the world through our senses, our meditations on them. It can blend all of our senses together in one synesthetic, cathartic moment of a poem. An old professor used to say poetry is “a compressed drama”. I tend to agree with that statement. The old maxim ‘a picture is worth a thousand words’ might be true in some cases, but poetry finds a way with words to tip the scales so a picture might be worth only a precious few.

I think it is true when people say that music is its own language. I’ve heard master musicians described as being “fluent in many idioms” (I think this was in reference to guitarist John Scofield) such as jazz, blues, funk and many other genres. The interesting thing here is the word “idiom”. This is a word that refers to written language; yet music has none in that sense, excluding musical notation of which not everyone is literate. Music communicates emotion as a sort of raw energy, directly through the ears; something that also happens in the best kinds of poetry. Songs ranging from classical to pop are regimented and structured: also in poetry. Lyrics can be, and sometimes are poems themselves.

One idiom that comes to mind is: “poetry in motion.” This may sound cliche, but the fact is that movement, gestures, and expressions are all ways to communicate: body language. When a dancer moves the feet and arms in a certain way, we are moved by the evocation, the emotional energy. When a ball player passes a ball with intent, the receiver knows where to be, how to get there: the coordinates have been communicated, all without words. Yet when the actions are completed, when a hole-in-one is scored or a masterful trick landed on the rink, the highest praise we give is in terms of poetry.

If poetry has a place in the lexicon of popular culture, then it is something that can be written, revised, and revamped. More readers, from all ranges of experience, could and should turn to poems for pleasure, for inspiration, for healing; to explore new worlds and perspectives in a few short lines. On the other hand, poets should perhaps be conscious of a wider audience when writing poems as to make them more accessible.

I apologize for rambling on. I would love to hear anyone’s thoughts on this very free and open discussion in the comments section below. Cheers!

Author:

Jason Ryou

Editorial Board Member

Jason Ryou is an MFA student at Hamline University. He has lived in Glasgow, Los Angeles, and Seoul, and currently resides in St. Paul.

Jason Ryou is an MFA student at Hamline University. He has lived in Glasgow, Los Angeles, and Seoul, and currently resides in St. Paul.

In The Field: Conversations With Our Contributors–Tyler McAndrew

In The Field: Conversations With Our Contributors–Tyler McAndrew

Photo Credit: Heather Kresge

1. Tell us about your short story in Volume 20. How did it come to be?

A pretty huge percentage of the stories that I write begin as things that I just think are funny, just little jokes that I’m telling to myself. Initially, the only thing I knew about “How I Came to See the World” was that I wanted to write about someone having a pet skunk. For whatever dumb reason, I thought that was just hilarious. So, most of the early work that I did on this story was just figuring out what kind of a person would want to own a skunk. Somehow, the paragraphs about the neuroscience study found their way into the story–those were based on an actual research study that I participated in when I was a grad student and didn’t really have enough money to afford anything beyond my rent.

2. What was an early experience that led to you becoming a writer?

My older brother, Phil McAndrew, is a cartoonist and an illustrator, and when we were growing up, we always used to draw comics with our friends. I always imagined that I would end up having a career in comics. But I was never crazy about super-heroes or action stories, and that stuff dominates so much of comic culture, and in retrospect, I think part of me was always kind of exhausted by comics. I never thought of myself as a writer though, and it wasn’t until I was a senior in college and took my first ever writing workshop, with Phil LaMarche, that it began to feel like a thing I wanted to do. Phil was a fantastic teacher, and on some level, I think that I owe him some thanks for all of the writing I’ve done since then.

3. How has writing shaped your life?

In the most concrete terms, writing has helped me get jobs as both a tutor and a teacher  (my primary sources of income for the past several years). I try not to be too spiritual or grandiose about writing, but I do also think that, while I’ve lived a much different life from either of the characters in “How I Came to See the World,” writing has helped me with a lot of the same things they’re struggling with: being honest, setting goals, and trying to find some purpose or meaning in my life.

(my primary sources of income for the past several years). I try not to be too spiritual or grandiose about writing, but I do also think that, while I’ve lived a much different life from either of the characters in “How I Came to See the World,” writing has helped me with a lot of the same things they’re struggling with: being honest, setting goals, and trying to find some purpose or meaning in my life.

4. What books, writers, art, or artists inspire you and your work?

Carson McCullers has always been one of my favorite writers. Her second novel, Reflections in a Golden Eye, was probably the first book I ever read that made me feel like, “yeah, this is the sort of book that I want to write.” Amy Hempel and Stephanie Vaughn are a couple of other writers whose stories I always look to as the sort of thing I want to strive for. I’m always inspired by my friends, too. My friend Cameron Barnett just published his first book, The Drowning Boy’s Guide to Water, which is a collection of really beautiful poems, and being at his book launch reading in Pittsburgh last year–just seeing him, seeing that all of this is possible and that it’s all worthwhile–was easily the most important literary event of my recent life.

5. What projects or pieces are you working on right now?

There are always at least five or six things that I’m rotating between. I’m hopefully getting close to finishing a manuscript of short stories. The story that’s been demanding my attention this past month or so is about a haunted house. I also have a nonfiction piece that I’ve been working on for several years about a woman who lived her entire life off the grid, in a house out in the woods–about an hour north of where I live in Pittsburgh–without running water, heat, or electricity.

Visit Tyler’s website and follow him on Twitter.

Early Bird Writes the Book: An Interview with Author and Hamline Grad, Lucie Amundsen, on the Benefits of Early Morning Writing, By Jessica Lind Peterson

Early Bird Writes the Book: An Interview with Author and Hamline Grad, Lucie Amundsen, on the Benefits of Early Morning Writing, By Jessica Lind Peterson

I wish I was a morning person. I really, really do. I wish I rose early enough to witness the morning sun kissing the horizon on its way up, to hear the birds early morning chatter. But I am not a morning person. Not even a little bit. I’ve tried everything from programming the coffee pot timer, setting multiple alarms, going to bed early. I’ve threatened and chastised myself. I’ve even bribed myself with doughnuts. But it’s hopeless. I like to sleep. As a writer/mom/theater producer/full time graduate student I recognize my anti-morning attitude is not ideal. I constantly feel behind in my work and wish there were more hours in the day. I could get a lot more writing done if I could just get my butt outta bed before the kids woke up.

Since I’m a serial snooze-pusher and have no actual wisdom to offer, I turned to early bird writer and recent Hamline grad,  Lucie Amundsen (MFA ‘14), for inspiration. A Duluth-based writer, Lucie started an industry-changing egg farm, worked a day job, raised two small children and got her MFA all while managing to write the beautiful, award-winning book, Locally Laid. Lucie is my hero. Also, who better to be the star of my Early Bird Blog Post than an author who actually writes about birds? You’re welcome.

Lucie Amundsen (MFA ‘14), for inspiration. A Duluth-based writer, Lucie started an industry-changing egg farm, worked a day job, raised two small children and got her MFA all while managing to write the beautiful, award-winning book, Locally Laid. Lucie is my hero. Also, who better to be the star of my Early Bird Blog Post than an author who actually writes about birds? You’re welcome.

Jessica: Have you always been an early bird writer?

Lucie: I’ll admit it; I’m a morning gal so getting up early just feels right to me. But conversely, I pretty much lose my sense of humor by 10:00 PM, so I pay the price at night.

Jessica: Do you have a special morning ritual that helps with grogginess?

Lucie: I love that special groggy part of that morning. I’ve re-framed it into thinking it’s a creative period. Am I just tricking myself? Probably, but that’s ok. Back in the 90s, I heard Kate DiCamillo talk on MPR about getting up very early to her preprogrammed coffeemaker and slinking over to her desk because she didn’t really want to fully wake up before starting to write. I took that to heart.

Jessica: What advice do you have for us snooze-pushers?

Lucie: If you leave off at a fun place in your project and go to sleep thinking how great it will be to get back at it, you might actually be jazzed about that special morning time. I stopped setting an alarm altogether when I was writing hard on the project. I was just that excited to work on it before the rest of the day rushed in on me. It was always sad when I realized I needed to start the family morning hustle and then go to work.

Lucie: If you leave off at a fun place in your project and go to sleep thinking how great it will be to get back at it, you might actually be jazzed about that special morning time. I stopped setting an alarm altogether when I was writing hard on the project. I was just that excited to work on it before the rest of the day rushed in on me. It was always sad when I realized I needed to start the family morning hustle and then go to work.

Jessica: Is your early morning writing time always productive?

Lucie: It’s almost always productive. I have to be careful not to get sucked into reading the news online or checking Instagram or Facebook. If I can stay off those traps, I usually write well.

Jessica: What time do you wake up?

Lucie: When I was finishing the book, I was up and writing at about 4:15 AM (I know, I know) but now that I’m bereft of a big juicy project, I’m sleeping until 5:30. I wake kids and start making lunches at about 7:15.

Jessica: Do early morning writers have to also be early go-to-bedders?

Lucie: Yeah…I’m usually in bed around 9:30 so I can read for 30 minutes. This writer’s life is not a glamorous one, but I like it.

There you have it. Thank you, Lucie, for inspiring us all to get our pa-tooties outta bed and make some morning magic. And while you’re up, do yourself a favor and read her amazing book, Locally Laid, published by Penguin Random House.

To learn more about the Locally Laid Egg Company and Lucie’s work, we highly recommend checking out the company’s website.

Author:

Jessica Lind Peterson

Editorial Board Member

JESSICA LIND PETERSON is a playwright, actor and founder of Yellow Tree Theatre in Osseo, Minnesota. She has been a finalist for the Loft Short Story Contest, the Loft Mentor Series in Creative Nonfiction and the Common Good Books National Love Poem Contest. Her essays have either appeared or are forthcoming in River Teeth, Alaska Quarterly Review and Anomaly. She is an MFA candidate in Creative Writing at Hamline University. Visit her website here.

JESSICA LIND PETERSON is a playwright, actor and founder of Yellow Tree Theatre in Osseo, Minnesota. She has been a finalist for the Loft Short Story Contest, the Loft Mentor Series in Creative Nonfiction and the Common Good Books National Love Poem Contest. Her essays have either appeared or are forthcoming in River Teeth, Alaska Quarterly Review and Anomaly. She is an MFA candidate in Creative Writing at Hamline University. Visit her website here.

In The Field: Conversations With Our Contributors–Chelsea Dingman

In The Field: Conversations With Our Contributors–Chelsea Dingman

1. Tell us about your poem in Volume 20. How did it come to be?

My poem, “Aftermath,” was written the night of the election in 2016. I was in the process of writing a poetry collection about women who have suffered infertility and I had read some very negative comments about women in power online as I was following the election coverage. It made me think about the word “miscarriage” and all of the ways that a woman might suffer miscarriages over the course of one’s life. I was also feeling very discouraged about the possibilities for women: what we will be able to achieve and not achieve in my lifetime, in my children’s lifetime. The loss of the child and the loss of power became the backdrop for this greater negation of possibility for women.

My poem, “Aftermath,” was written the night of the election in 2016. I was in the process of writing a poetry collection about women who have suffered infertility and I had read some very negative comments about women in power online as I was following the election coverage. It made me think about the word “miscarriage” and all of the ways that a woman might suffer miscarriages over the course of one’s life. I was also feeling very discouraged about the possibilities for women: what we will be able to achieve and not achieve in my lifetime, in my children’s lifetime. The loss of the child and the loss of power became the backdrop for this greater negation of possibility for women.

2. What was an early experience that led to you becoming a writer?

My father died in a car accident, the winter that I was nine. I had the most wonderful homeroom teacher at the time. She encouraged me to write. I wrote her a book of poems about snow. When she liked it, I tried to write her a novel. That went less well, but it made me realize how much I loved the process of writing.

3. How has writing shaped your life?

I have always been an avid reader. I enjoy reading more than any other activity. Other writer’s words change the way that I look at and respond to the world. I write almost as an aside to that, or as a response to the excitement of what I’ve read, and the possibility that language offers.

I have always been an avid reader. I enjoy reading more than any other activity. Other writer’s words change the way that I look at and respond to the world. I write almost as an aside to that, or as a response to the excitement of what I’ve read, and the possibility that language offers.

4. What books, writers, art, or artists inspire you and your work?

There are so many (and I know that’s a cliché answer). A few poets whose work I so admire: Patricia Smith, Aracelis Girmay, Larry Levis, Li-Young Lee, and Louise Glück, along with many poets in translation, such as Czeslaw Milosz, Anna Akhmatova, and Wisława Szymborska.

5. What projects or pieces are you working on right now?

For my next collection of poems, I am researching traumatic brain injury in professional athletes, including CTE, which can only be diagnosed upon autopsy. Some of the research will be anecdotal in that I am examining the effects on both the individual and the family members.

Visit Chelsea’s website, follow her on Facebook, and follow her on Twitter.